In the final blog of a three-part series, Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research researcher Agajie Tesfaye looks ahead and provides seven key recommendations on how the Ethiopian government can lessen the negative impacts of COVID-19 restrictions on day labourers, farmers and rice commercialisation. Look below for the previous blogs:

Part one: Presents preliminary findings and statistical analysis of research assessments.

Part two: Examines the effects of COVID-19 on labour wages, service providers to labourers and rice production.

Read more on the Impact of COVID-19 on Food Systems and Rural Livelihoods in Ethiopia in the Round One and Round Two APRA country reports.

Read the full APRA synthesis report on the Rapid Assessment of the Impact of COVID-19 on Food Systems and Rural Livelihoods in Sub-Saharan Africa, here.

Written by Agajie Tesfaye

Looking Ahead

COVID-19 has started impacting the labour markets in the rice plain of Amhara Region. Labour markets have been deserted because of government restrictions to keep physical distancing and prohibition to stop in groups at a specific point. Rice farmers can’t obtain an adequate number of daily labourers for rice weeding and other operations. Some farmers are adopting the following temporary solutions:

- Mobilising all their working age family members;

- Using chemical sprays to control weeds, despite its limited effect;

- Using hired labour from nearby areas.

These temporary solutions may not be helpful when the acute labour demand season commences – and in response to high demand and limited supply – the labour wage has also increased by about 30%. Almost all the rice farmers will be looking for hired labour towards mid-August for second rice weeding and also for harvesting in later season.

Family labour will not meet the demand for weeding and harvesting within critically labour demand periods. Rice production and productivity could be negatively affected if this work is not done on time, indicating the extent to which rice farming was dependent on hired labour.

In response to the surge in COVID-19 and the rise in fatality rates in Ethiopia and government restrictions on movements, the availability of hired labour will continue to be scarce in the coming high labour demand months. Labour dependent economic sectors and farms will be largely hit by the sweeping of the virus. Without the use of supplementary hired labour, rice production and productivity will be compromised substantially. Production decline will in turn affect annual incomes of farmers reducing further investments on rice. Rice processing sector will also be affected because of limited production supplies. If the pandemic continues to persist in the coming seasons, rice farmers have indicated that they will reduce the area allocated to rice by 40 – 50% to the extent it is manageable only by family labour. This all implies that rice commercialisation will be affected in response to prolonged spread of COVID-19 in the country. It is likely to happen unless effective vaccination is discovered and accessible to all the population.

Policy considerations

- Easing Restrictions: With no social insurance policy (paid unemployment) in Ethiopia and social assistance (cash or in-kind transfers) unavailable in many locations, the government will have to ease restrictions imposed during the state of emergency. Even though lockdowns could help to reduce the spread of the pandemic, it is also negatively impacting on the economy and exacerbating poverty. While easing restrictions, strict measures should be imposed to use PPE while away from home.

- Providing adequate information about the pandemic: Awareness creation on the severity of COVID-19 disease and its complicated features need to be promoted for daily labourers and other community members on sustainable basis. Simple approaches such as microphones at market places and across main roads in towns could work. The mass media could also make use of easily understandable people centred approaches, such as local television dramas. The approaches should be renewed and replaced with new ones every time to avoid negligence from the audience.

- Mandatory rules and enforcement by local administration: Local government officials should also impose mandatory rules and enforce daily labourers to use face masks and socially distance at labour markets. Employers could be told not to hire any labourer without a mask, and enforce distancing at their workplace.

Local officials should also impose mandatory regulations on local service providers, such as room rental service providers and restaurants. While offering their services, they must enforce physical distancing, and should be forbidden from providing accommodation to groups of labourers. Officials should randomly inspect these premises and inform them that they are accountable for any violation of the rules.

- Self-equipped Labourers: Employers should only be allowed to hire labourers who bring their own hand tools, such as sickles, to minimise transmission of the virus.

- Imposing and exercising strict accountability measures: Strict accountability measures, such as fines or temporary detainment, should be enforced for repeated violations of regulations to ensure everyone’s wellbeing, as many informal workers may be at risk of contracting COVID-19. Therefore, protective measures should be strictly implemented and used as per the advice of Ministry of Health and other institutes.

- Widespread provision of masks, hand washing stations and sanitisers: Many members of the community cannot afford PPEs, especially in district towns. Efforts should be made to install hand washing stations along with detergents and sanitisers on the road sides and entry points. Masks should be given out for free or with very little cost for poorer members of the community.

- Switching to agricultural mechanisation: Improvements to weeding, harvesting and others technologies should be demonstrated and promoted to farmers.

It may be too late in the short term as the season has already started, but it should be promoted when the harvesting season begins in four months. Ministry of Agriculture, agricultural research institutes, high learning institutes and other development partners need to provide similar training for farmers on how to operate and access the rice harvester machines.

In the long run, agricultural research institutes and other organisations need to strengthen and provide due focus in developing small-scale agricultural machines for various operations, such as rice planters, weeders, harvesters and threshers. The government should also strengthen its supports for mechanisation of agriculture sector, such as duty free importation, credit, hard currency and other services.

References (all three blogs)

Agajie Tesfaye, Abebaw Assaye, Degu Addis, Tilahun Tadesse, Dawit Alemu and John Thompson. 2019. Rice Commercialization and Labour Market Dynamism in Fogera Plain: Trends and Prospects (Unpublished).

Degye Goshu, Tadele Ferede, Getachew Diriba, and Mengistu Ketema. 2020. Economic and Welfare Effects of COVID-19 and Responses in Ethiopia: Initial insight. Policy Working Paper 02/2020. ISBN 978-99944-54-74-7.

Karmen Naidoo. 2020. The Labour Market Challenges of COVID-19 in Sub-Saharan Africa. https://www.africaportal.org/features/labour-market-challenges-covid-19-pandemic-sub-saharan-africa/

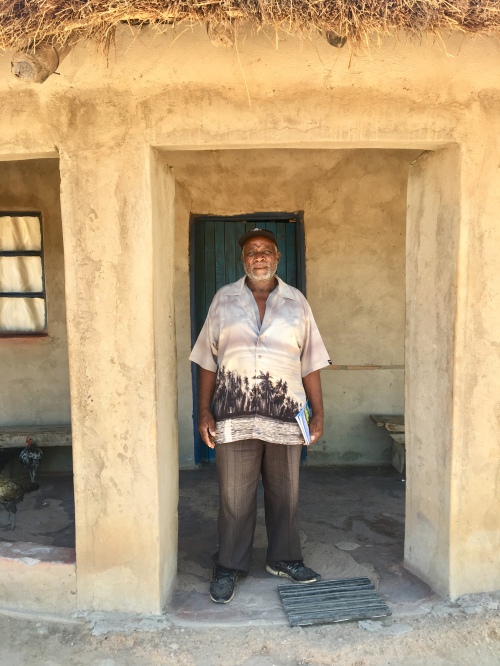

Cover photo: Labour market during pandemic. Credit: APRA Ethiopia

Map: Showing Amhara region. Fogera is located on the east side of Lake Tana. Source: Map data @2020 ORIEN-ME, Google.

Please note: During this time of uncertainty caused by the #COVID19 pandemic, as for many at this time, some of our APRA work may well be affected in coming weeks but we aim to continue to post regular blogs and news updates on agricultural policy and research.